www.w-ch-klose.de |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Naturwissenschaft, Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Almanac of Six Jewel Rivers

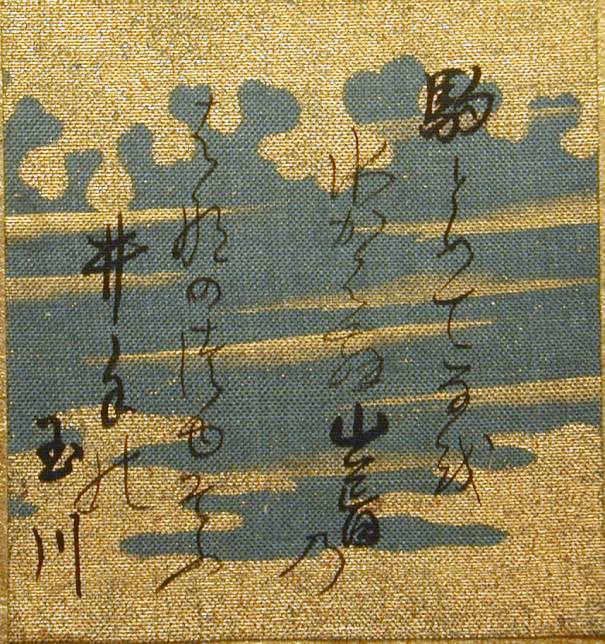

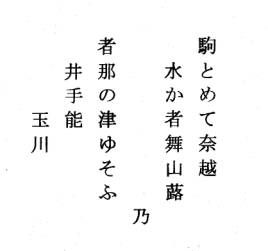

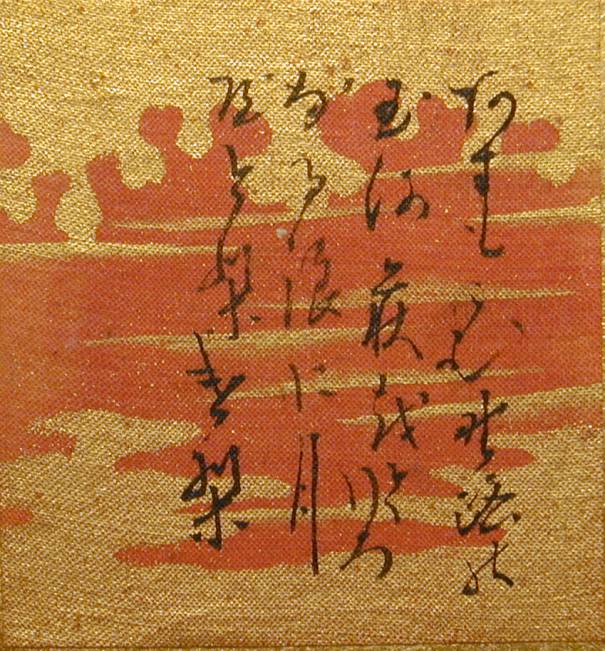

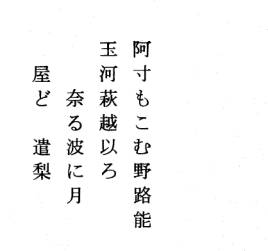

Poem No. 1 (Murase 4) This poem was written by Fujiwara no Shunzei (Kôtaigôgû no Daibu Shunzei, Toshinari, 1114-1204). It appears as No. 159 in the 2nd book of the „New Anthology of Ancient and Modern Japanese Verse“ (Shin Kokin Waka Shû), compiled 1205 by Fujiwara no Sadaie at the order of the retired emperor Go-Toba. Pulling up my horse The Kokin Shû (A Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern) was the first official collection of poems, compiled by Ki no Tsurayuki in 905 on order of emperor Daigo. It covers 1100 poems and has a preface of Ki no Tsurayuki (883-946) written in Kana, as well as an epilogue in Kanji by Ki no Yoshimochi. The preface is the first account of appreciation of poetry in literary circles in Japan.

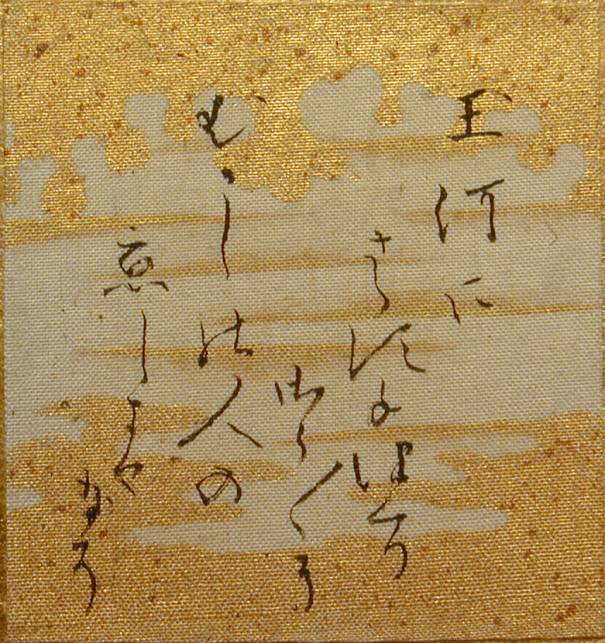

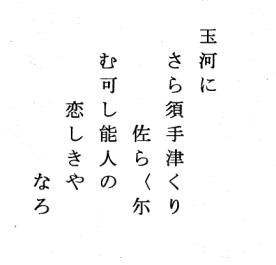

Poem No. 2 (Murase 5) This poem originates from Sagami, a famous poetess of the 11th century. She was a daughter of Minamoto Yorimitsu, married to Ôe Kinsuke, Sagami no kami, whence the name under which she is known. The poem is recorded as No. 175 in the Shûi Waka Shû (Waka-Gleanings; compiled in 1001) I see the waves Unohana (Deutzia scabra) is a deciduous, sunflower-like shrub. The Tamagawa cited here runs near the city of Sato. Miyeko Murase identified this river instead with the Tamagawa at Kinuta (present day Ôsaka), following the painting on the scroll in the Burke collection, which shows people who are fulling cloth.

Poem No. 3 (Murase 3) This poem is by Minamoto no Toshiyori (1055-1129), contained as No. 281in the Senzai Waka Shû (Anthology of a Thousand Years of Japanese Verse, compiled circa 1188 by Fujiwara no Shunzei at the order of the retired emperor Go-Shirakawa,). I shall come back again tomorrow The river Noji no Tamagawa (near Kyôtô in the province of Ômi), also called Hagi no Tamagawa is famous for its moon-viewing. Hagi is the Japanese bush-clover, Lespedeza bicolor, a plant with small purple or white flowers that bloom in autumn, was popular among poets since the Manyô shu times.

Poem No. 4 (Murase 2) This poem by Fujiwara no Teika (Sadaie, 1162-1241) is contained in his own collection of poems „Gleanings of Humble Weeds“ (Shûi Gûsô Shû, No. 860) of 1233. The cloth that is hung over The river Tetsukuri no Tamagawa was known for its fabric-bleaching industry.

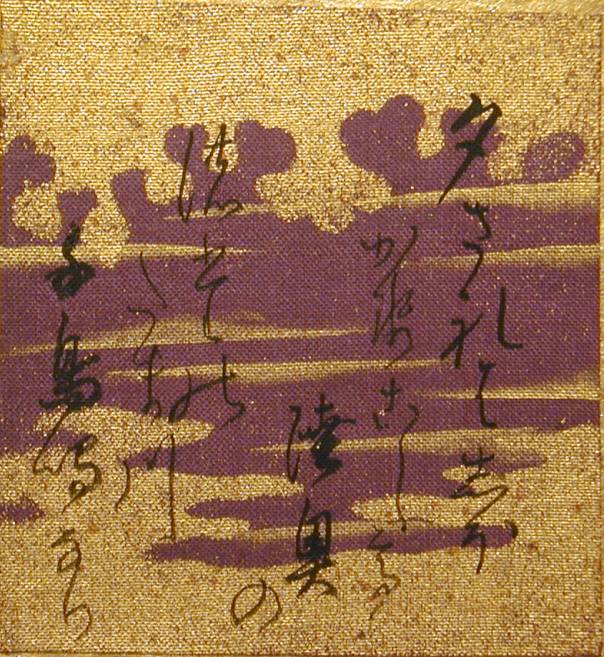

Poem No. 5 (Murase 1) This poem by Nôin Hôshi (988-1050) is No. 643 in the 6th book of the Shin-Kokin-Shû. When the evening approaches The river Noda no Tamagawa near Sendai (formerly the province of Mutsu, present day Miyagi) was famous for plovers and fresh green leaves.

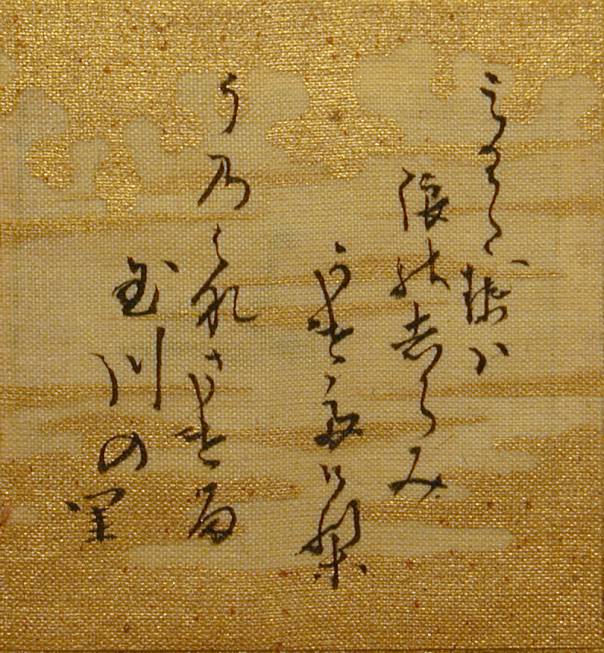

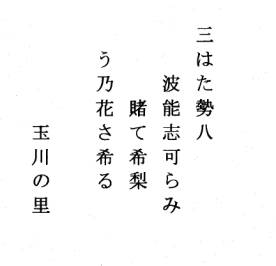

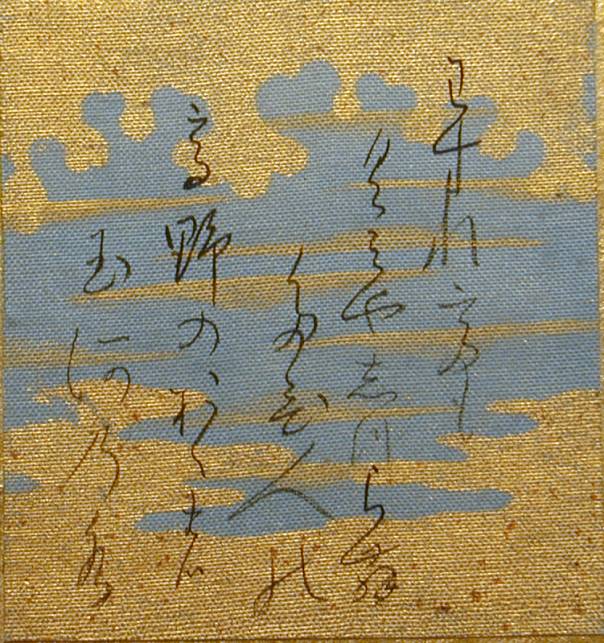

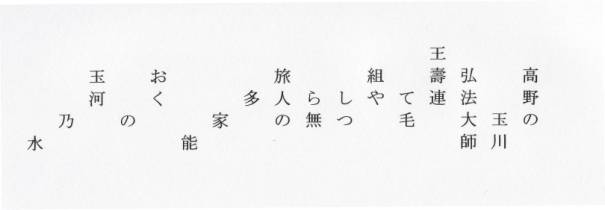

Poem No. 6 (Murase 6) This poem by Aichi Shônin is part of the anthology Fûga Waka Shû (Collection of 2201 Graceful Poems, No. 1788), prepared by the retired emperor Hanazono as the 17th official collection of poems. Hanazono (1297-1348) lived after his abdication 1318 under the priest’s name Hengyô in the Zen temple Myôshin-ji in Kyôtô, in a quarter named Gyokuhô-in. Since the water of the Tamagawa at Mt. Kôya was infested by poisonous insects near the source of the river, it would have been dangerous to drink. Therefore, a poster was warning the pilgrims not to drink water on the path of worship leading up to the Okuno-in (Inner Temple) of Mt. Kôya. Against all warnings,

Afterword The series of the six Tamagawa rivers comprises different aspects of human feelings about streams of water. The underlying appreciation, of course, comes from its drinking qualities. But streams provoke much more sentiments. Poem No. 1 recalls a phenomenon of natural beauty, when the petals of roses are spread over the river’s surface. Poem No. 2 indicates, that water-waves eventually also may become dangerous. However, as long as engineering skill can construct a dam or a weir and keep it, people behind that may dwell in peace. Poem No. 3 recalls the deep feelings of Japanese when the moon lights up the darkness of the night, especially when it is mirrored in a quiet water. Poem No. 4 shows, that rivers help people with their industries. Poem No. 5 reminds the listener, that there are also other creatures living and depending on water, especially on rivers flowing freely in nature. Poem No. 6 suggests, to test the water before drinking it. Thus, the Mu Tamagawa poems are not just six poems collected on occasion of the inauguration of a new water supply for Edo. Instead, they are carefully chosen to express a general moral, a Buddhist moral: No thing only has one side. Each and every thing instead has positive and negative features. In our case we have to remember, that streams on one hand are beautiful, useful and helping, but they may on the other hand also be wild, dangerous and poisened. May be, that the poets have been widely unknown in the middle of the Edo period. The poems, however, were well known and considered as a legacy from the highly appreciated Heian period. Our small almanac with the collection of the six poems, written in a beautiful calligraphy may have served for its owners as a source for deep thoughts and meditation.

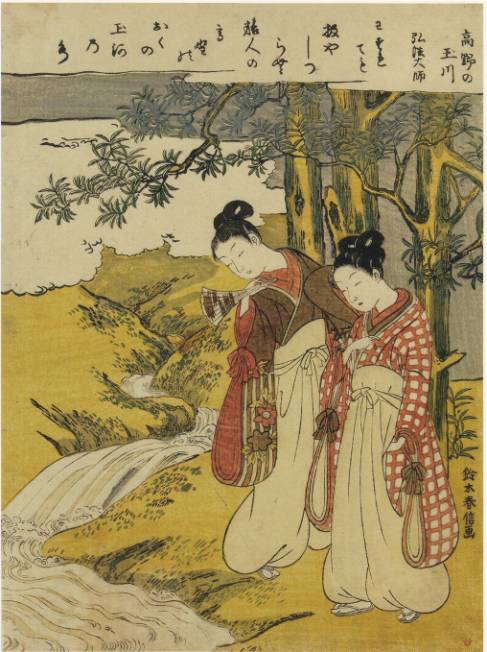

Appendix Mu Tamagawa and Ukiyo-e The six Jewel Rivers were a popular topic for ukiyo-e artists in the Edo period. Among them Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770) was an author of such prints. Around 1768-1769 he issued a “mitate” print, chuban format (27,3 x 20,4 cm), signed Suzuki Harunobu ga, which appeared as lot 31 in Sotheby’s sale in Paris of the Huguette Berès collection of Japanese prints, drawings and illustrated books, part 2, 25 November 2003. It was sold for 9.600,00 Euro.

Mitate-e 見立て 絵 ("look and compare pictures"). Harunobu did not picture the real situation of pilgrims on Mount Kôya. He followed a custom of his time and made a parody, a travesty, called mitate. Such a picture offers imaginative, simultaneous, and multiple layers of meaning. 'Mitate' was a metaphorical, often playful or ironic way, that linked the contemporary with historical events, tradition, either in recent or distant past, mostly quotation from highly respected tradition or even religious ideas. The obvious parody here comes from the fact, that Mt. Kôya was off limits for each and any female . The two beauties are only faibly disguised with large trousers (hakama) and do not wear any object of pilgrimage. They are virtually impossible at Mount Kôya's Jewel River. As a westener one might think, that the picture contains a simple rule of life: although, even if one knows quite well, that there is some danger, nevertheless one likes to try. What dangers the two beauties will meet? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||